This post may contain affiliate links. We may earn money or products from the highlighted keywords or companies or banners mentioned in this post.

I needed a distraction, and, god help me if the majesty of Angkor Wat didn’t work.

The bike I rented was white, or, at least, it had been once. It had the scrapes and dents of an accident-prone life, but it was sturdy and I liked the way the long handlebars curved toward me like open arms. I rode out on the main road, and soon dense trees and monkeys sunning themselves in the dirt replaced the hotels and shop stalls.

I stopped to snap a few photos of the monkeys who came close, hoping for food. Eight of them formed a circle around me. They had done this before. There was no question I was the focus of their attention, but they refused to look directly at me. I was sure it was deliberate, the way you avoid staring directly at the sun. They kept their gaze steady, looking just to the side of me, as if I had toilet paper stuck to my shoe. They were no larger than fat housecats, but those opposable thumbs were intimidating. They did not beg. They were still. Silent. It was a clear, sunny morning, and I could see people not far off, but in those moments I would not have been surprised to die by monkey.

I had a couple of chocolate chip cookies in my bag, and I got them out slowly, breaking them up and tossing chunks away from my bike and me. Several of the monkeys ran to investigate the cookies, but a few stayed just as they were – watching but not watching. I stepped backward toward my bike as one of the monkeys presented a handful of chocolate chips to the monkey who stood closest to me and on highest alert. Amazing. He had eaten around the chocolate, saving the chips for his monkey master. Still watching the monkeys, I felt for my bicycle seat behind me and quickly got on, pedaling fast. I didn’t look back.

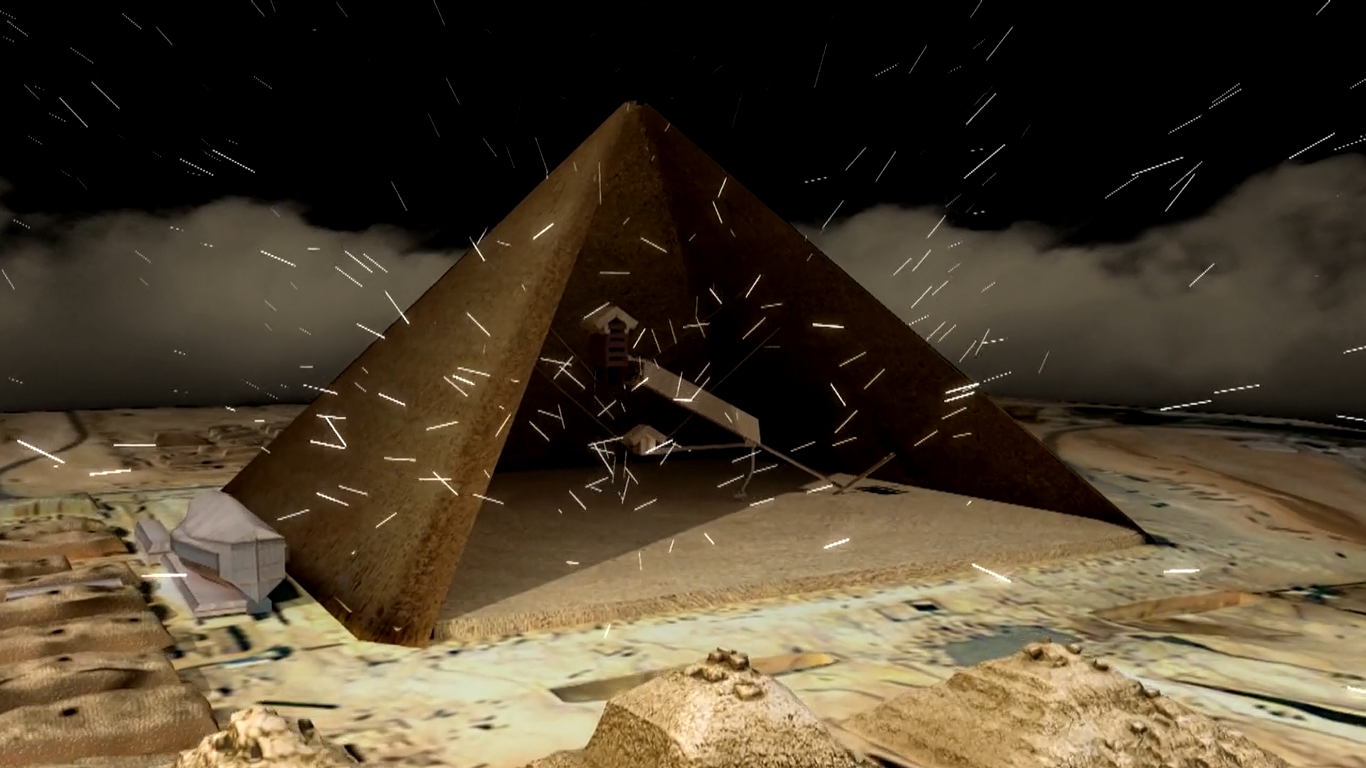

The city smells of gasoline and sweat faded, and the air turned sweet and damp. I was close. A fork in the road, and I veered left. The stone entrance to Angkor Wat rose before me. It was sweeping and imposing, yet it blended into the land and the trees as if it had always been there, as if it weren’t man-made at all. I had the feeling that the temple was both above and below ground – twins, reflecting back at each other, one in front of me and the other beneath me, steadying me. I envisioned the stones with thick roots, pushing themselves deeper into the soil and coiling around one another.

The entrance was still another quarter of a mile, but I pulled over and sat down on the grass. This was my father’s dream. He had swept me up into it as soon as he uttered the unfamiliar words Angkor Wat, and I tried it on eagerly like I was playing dress-up. But then I never took it off. And even though his dream was soft against my skin, it was too big and too heavy and it dragged behind me and hung loose at my waist and wrists, shapeless. I was terrified I wouldn’t understand my father’s Angkor Wat, wouldn’t see it or feel it the way he had wanted to, because I had no idea what he’d been hoping to find. If he ever told me, I forgot. I had no idea where he heard about Angkor Wat. No clue what attracted him to it. What I do remember is his excitement at the thought of being here. I wasn’t used to adults being excited about things, especially not my dad, who was hard to impress. Something about Angkor Wat had impressed him, though.

Until that moment, I hadn’t realized that a part of me had been hoping Angkor Wat would be a letdown. If it were not as great as everyone said it was, then it would have been all right that my father never got to see it. But here it was, exceeding my expectations with stunning power and grace. I thought about my father, the architect, who saw fields and parking lots as blank canvases just waiting for his drafting pencil. He never saw what was actually there, only what could be. When we biked by vacant lots, all dirt and weeds and fast food wrappers, my father would describe the different ways he’d maximize the space and the views and where he’d put windows and why he’d slant one portion of the roof or another. In the years since his death, houses and office complexes have sprung up in those empty spaces, the fulfillment of some other architect’s vision.

The quincunx of stone towers at the center of the temple looked bold and strong against the blue sky, and it seemed impossible that they had ever not been there. In their shadow, the spindly sugar palm trees looked like the flimsy man-made additions. My father would have loved the idea of man doing nature one better.

He had taken me once to a marble yard. He was looking for marble for the island in his kitchen. We found the one he wanted—a deep gunmetal color. Rippling through it were streaks of rock in shades of ruby and diamond. The slab, rough and jagged along its edge, was huge, several times taller and wider than I was. It had been propped up against a wall in the large, dusty yard; it was too grand for its surroundings. I pressed my palm flat against its smooth surface and was surprised to find that it was cold.

“It’s beautiful,” I told him.

“Yes,” he replied and smiled at me.

I felt as though I had passed a test.

“What will happen to the edges? Will you make them smooth?” I asked.

“Most people do.”

“I think you should leave them like this, smooth on top and bumpy around the sides,” I said.

He nodded. He listened. He designed the island in the shape of a wedge and had a hole made in one corner where the marble came to a narrow point. At his request, the workmen put a pole through the hole and attached a wrought iron wheel to the end of it. In the center of the island he installed a removable clock that was flush with the surface; when you popped it out you discovered a hole with a hidden electrical outlet at the bottom. You plugged a toaster or other kitchen appliance into the outlet and this way the cord was inconspicuous and out of the way. My father found cords and wires unsightly; whenever possible life should look effortless. And the edges, all the way around the island, were just as rough and bumpy as they had been at the marble yard.

I wandered through the gopuras and galleries of Angkor Wat all morning and into the afternoon. It was cool in the shaded passageways and for long stretches of time I encountered no one else. The temple was filled with solitary stone statues of Buddha whose heads had long been lost, but my eyes swept past them. I followed the apsaras: female spirits of the clouds and waters who appeared to be dancing right off the walls in elaborate headdresses and jewels that traced the curve of their chests and hips. They are sometimes said to be the caretakers of fallen heroes. Elegant and strong, every detail of their appearance is well considered. They take care both of themselves and others. I think of caretaking as a solitary act, but the apsaras I saw were almost never alone, appearing in pairs and groups of three or four like sisters, like family.

I ran my finger along the letters and numbers that had been carved into blocks and pillars. I walked down and up crumbling staircases that led to nowhere. I peeked through cracks and empty windows to watch men skim enormous, flapping leaves off the surface of the pond outside. They laid them flat, one on top of the other, in the back of their carts. The leaves looked like water lilies without lotuses, and I recalled the lilies my father often kept in a tall black vase on his dining room table.

Much of the bas-relief depicting the Churning of the Ocean of Milk was closed for restoration but not all of it. I sat cross-legged on the floor looking up at the gods, called devas, and the demons, called asuras, using the serpent king to churn the ocean and release amrita – immortality. According to mythology, it took them a millennium, but they eventually got their immortality. They also released poison, wealth, poverty, the moon, a white elephant, a horse and a genie tree that granted desires. In the depiction at Angkor Wat, the gods and demons are identical and work in unison. They are the same.

Everything I was seeing, I imagined my father saw, too. My eyes were his eyes. I guided him down every hallway and turned every corner, determined that he should miss nothing. I walked through “elephant gates” – entrances so big it was easy to imagine the regal animals parading through them. I looked up at ceilings covered in lotus designs and others where the sky shone through cavernous holes. Wall, roof and floor had crumbled in places and everywhere stone was eroded and deteriorating, creating shadows and depth, ghosts, a heightened sense of two worlds almost touching.

About the author: Victoria Loustalot, author of This is How You Say Goodbye, earned her BA and MFA from Columbia University and has written for The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Onion, Publishers Weekly, Women’s Wear Daily and Glamour, among others. She is currently working on her second book.

Where do you rank in our tribe of worldly readers? Answer these questions to get a sense.