This post may contain affiliate links. We may earn money or products from the highlighted keywords or companies or banners mentioned in this post.

Looking at Slovenia’s Soča Valley today, with its aquamarine river rapids, waterfalls gently tumbling down steep cliffs and dense, overgrown emerald forests, I had a hard time imagining that the area once resembled the barren and grey Soča Valley of Ernest Hemingway’s novel, A Farewell to Arms:

“There was fighting for that mountain too, but it was not successful, and in the fall when the rains came the leaves all fell from the chestnut trees and the branches were bare and the trunks black with rain. The vineyards were thin and bare-branched too and all the country wet and brown and dead with autumn.”

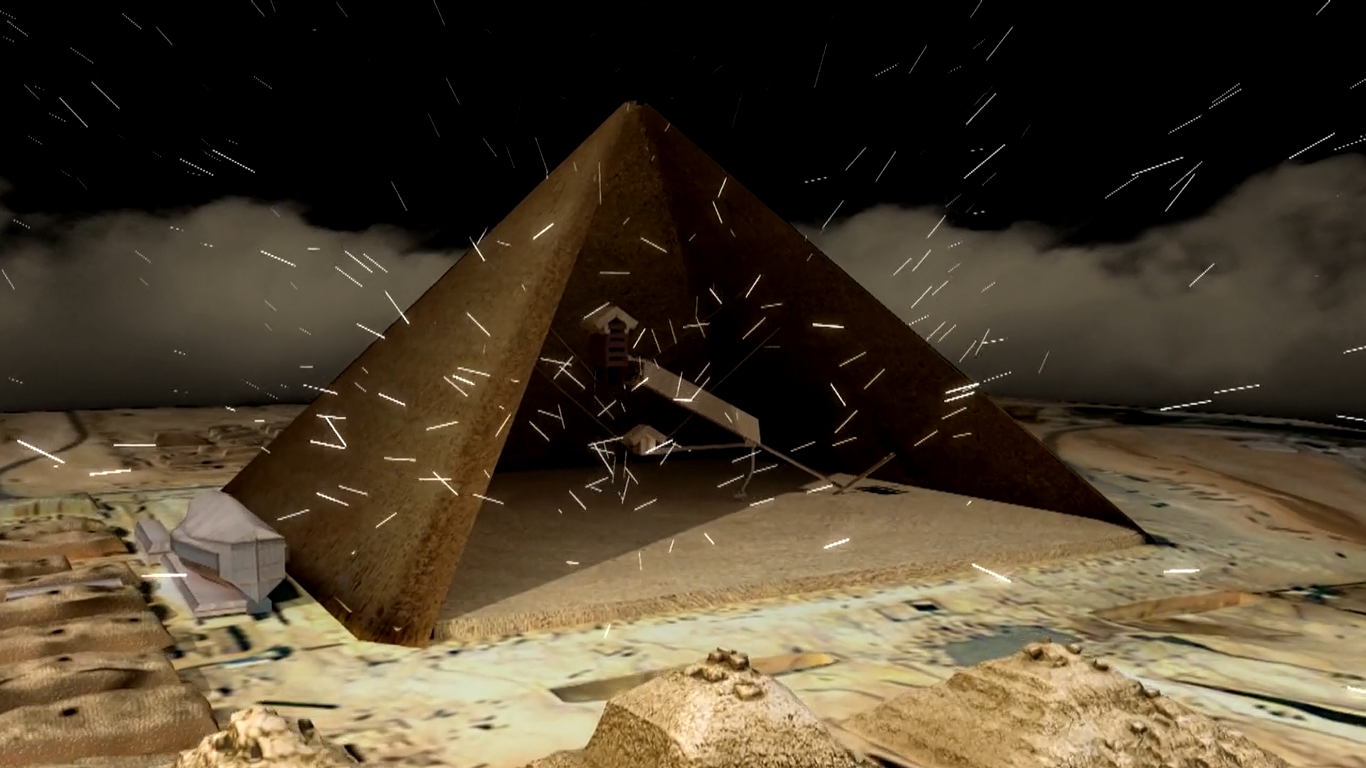

What’s even more difficult to imagine is that the valley was once part of the Isonzo Front, one of the bloodiest frontlines in WWI. Approximately 1.7 million soldiers died or were mutilated for life fighting on the Isonzo Front, many losing their lives attempting to navigate the steep mountain slopes, fight through whiteout blizzards or traverse unsurpassable canyons.

“The Soča Valley – and the Bovec area in particular – is unique because of its microclimate,” said my Soča Rafting guide Jure Črnič. “With the Julian Alps on one side of us, the Mediterranean Sea nearby, the Bovec Basin and the deep canyons and rivers together, the weather can change quite suddenly – and with adverse conditions.”

- An aerial view of Bovec. (Alberto Biscaro/Getty)

During WWI, the Soča river (known in Italian as the Isonzo river) ran north-south along what was then the border of Austria and Italy, opening a new 600km front when Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary on 23 May, 1915. A total of 12 major battles were fought there between 1915 and 1917, with the Italian side launching 11 of the 12 offensives. Despite the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s efforts to refurbish the old mountain pass defensives and fortify the jagged mountains that flanked its side of the river, the Allies eventually won WWI, causing the land that is now modern-day Slovenia to be annexed to Italy under the 1920 Treaty of Rapallo.

During the Battles of the Isonzo, many of the Soča Valley’s 300,000 residents were displaced to central Austria-Hungary to avoid the crossfire of the front line, while others were forced to relinquish their homes for soldiers’ barracks. Countless residents never returned, and for the thousands of soldiers who were transported to the region and died there, few records or traces of them remain.

In the years that followed, the region underwent even greater transition, and many of the old WWI sites were left to decay in the wilderness. Italianization turned into occupation by Nazi German forces, and eventually the region was absorbed into Yugoslavia at the end of WWII. It wasn’t until 1991 that the Slovenes won independence, and today, many Soča Valley residents have turned to adventure and cultural tourism to make a living.

In particular, a foundation known as the Ustanova Fundacija Poti Miru v Posočju is working to prevent WWI’s mark from disappearing. It collaborated with the Institute for the Protection of Cultural Heritage to create the Pot Miru, or “Walk of Peace”, a 90km-long trail that divides some of the major sites of WWI and the natural highlights of the Soča Valley into five one-day sections.

- One of the Soča Valley’s natural highlights. (Kirsten Amor)

The walk’s first section stretches approximately 11km, from the town of Log pod Mangartom to the open-air museum of Čelo, a former Austro-Hungarian artillery fortification just north of the town of Kal-Koritnica. I joined the trail about 5.4km south of Log pod Mangartom, at Kluže fortress, which has excellent vantage points of the Koritnica river gorge.

Despite its strategic importance in defending the Mt Rombon mountain pass during the 1809 invasion of Napoleon, the Kluže fortress was outdated by the time WWI began, and it was partially destroyed by the Italian forces’ relentless artillery fire. The formidable grey stone structure that remains contrasts the peacefulness of the deep gorge and surrounding forests.