At dawn the bush comes to life. Birds sing, a lion roars and a tiny deer steps gingerly past my veranda. As the first rays of light touch the acacias, there is a soft voice by the canvas and a tea tray is set out. Soon after sunrise, I grab my camera and climb on an open-top Land Rover to set out on the hunt for animals. The safari experience is underway.

I’m in Zimbabwe but you could apply the same paragraph to any one of a dozen African countries and thousands of safari trips. It’s a gorgeous thing to feel so deep in the wilderness, with nature in the raw just a whisker away. But what we don’t see, not very often, is the underpinning behind this ravishing image. Who works there? Where does the money go? What, if anything, does the operation contribute towards the preservation of the wilderness it exploits? And how secure is the long-term future of that wilderness? I had come on a trip that offers just that: a chance to see, clearly, what lies beneath.

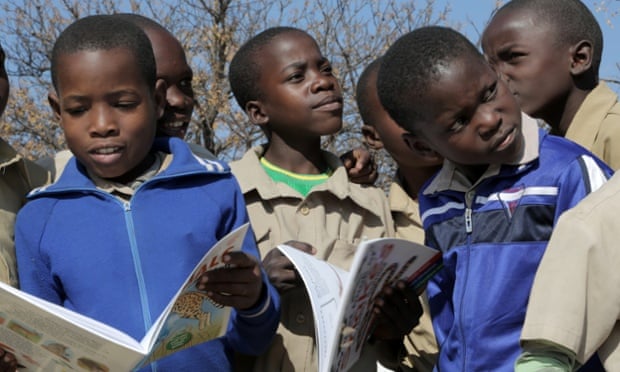

Later that day I am sitting in a Zimbabwean primary classroom with Vusa Ncube, an ex-pupil of the school, who has come back to encourage kids to study hard and become wildlife guides like him. He has a bird book and shows the excited children pictures. When he asks who would like to be a guide they all cheer. One of the girls says: “I want to be a driver!” But when the talk moves on to attitudes towards elephants and lions, the children tell stories of crops trampled and cows slaughtered. I ask if any of them have ever been inside the park? After all their school lies only a kilometre from the perimeter of Hwange, a large national park and a key part of the vast Kavango-Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area, the very heart of southern Africa’s wildlife. They shake their heads. None have even been there.

“>[embedded content]

Around a campfire that evening with some of the staff from Camelthorn Camp, I hear more about locals’ relationship with the park, or lack of it. Japhet and Zebra were born in Ngoma just on the park’s border. There was no electricity, a dilapidated school and no jobs. Poaching was the only means of living for many, but that usually ended in Bulawayo prison. “That was very hard,” says Japhet whose poaching buddy had died while they were locked up. Zebra took the desperate measure of walking to South Africa to find work, managing to survive for four years before the stress of being an illegal immigrant became unbearable and he walked home again. “The park was unpopular in those days,” they both say, “There was no benefit for us at all.”

Next day I’m out in the bush, searching for lions, cheetahs and wild dogs with Vusa and his boss, Mark “Butch” Butcher. A fifth-generation white Zimbabwean, Butch had spent years as a ranger in Hwange before deciding to attack the conservation problem at its root.

“These villages on the park’s borders have never seen anything but trouble from the wildlife. I’m convinced that we can’t achieve any lasting progress without involving the communities,” he says.

In 1998 Butch put his own savings into what everyone said was a doomed venture; he started a company called Imvelo (“nature” in Ndebele) and built a safari lodge, Gorges, on communal land outside Victoria Falls national park and made it policy to only employ locals. “We had a one-year lease but I built it with stone. I wanted the villagers to know I was in for the long haul. I live here too. There’s nowhere else for me to go.”

Zimbabwe’s descent into chaos between 2003 and 2008 brought the tourist industry to its knees, but with growing local support, Gorges survived. Now Butch is grasping the opportunity to expand, building Camelthorn deep in the bush on communal land close to Ngoma. Zebra got a job as roofer and his younger brother, Vusa, came along to see. “I saw this bright-eyed kid, full of energy and enthusiasm,” says Butch. “I asked him if he’d like to become a guide.” Two years later Vusa is into his final year of study.

In the park, beside a strolling herd of wildebeest and zebra, we rendezvous with another team bringing in plastic pipes and equipment. Butch wants to build a new small wilderness camp in a remote area called Jozibanini, which is close to the Botswanan border. “Last year we had a terrible poisoning incident when 130 elephants died.”

It is an isolated spot, unpatroled and vulnerable. The poachers brought poison from the gold mines and dropped it in the waterhole. “These are dangerous times for African wildlife. Believe me, ivory poaching could wipe out wild elephant stocks very quickly.” Statistics from across Africa back him up. Figures from CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) for 2013 reveal that about 20,000 elephants were illegally poached, almost all to feed an insatiable demand for kitsch ivory figurines in China. Chairman Mao statuettes are particularly popular.

On our way across the park to Jozibanini we stop and visit various waterholes. The park has an estimated 40,000 of them, all maintained by a system of boreholes that pump out millions of gallons of water every dry season. Elephants are everywhere in big herds. Each pump is guarded by two unarmed young locals, one of the most isolated and dangerous jobs in the world. “We bring in supplies for them,” says Butch, “Check that they’re OK.”

At one waterhole the pump attendants have built themselves a gym out of elephant bones, relics of drought not poaching. “I want to start a ‘pump-attendant-of-the-year’ prize,” says Butch, “Honestly, these guys are heroes.” In the remote waterholes the men can go for weeks without seeing anyone, their tin hut surrounded at night by lions.

“We sometimes drive the lions off their kill,” one of them tells me. “But that is an extremely hazardous way to get your meat!”

At Jozibanini I watch as Butch and his gang install new pipes for an underground pump and set the water running. Another work gang are building foundations for tourist tents. At night, under a vault of stars, we huddle around the campfire and they swap yarns about wildlife. The ex-poachers tell gleeful tales of gargantuan feasts on buffalo meat. “One time we killed eight buffalo, then drank so many beers we fell asleep.” They are all falling about laughing at the memory. “When we woke up all the meat was gone – eaten by our dogs.”

These men were never the type to hunt for ivory or rhino horn but their activities often had tragic consequences. The following evening Vusa and I visit a hide by another waterhole, a sunken shipping container that allows viewers to get incredibly close to wildlife as it comes to drink. We enter in daylight and wait inside. As dusk comes a distant rumbling is heard and then, without warning, an elephant strolls past my head. Silhouetted against the night sky we see a huge bull with half its trunk missing. “See that?” whispers Vusa, “He got tangled in a poacher’s snare – like my brother used to make.”

The bull kneels to suck water up, then stands to slosh it into his mouth. It’s a laborious and time-consuming task, but his determination to survive is strong. Having convinced local men like Zebra that poaching does not pay, Butch now fears that a deadlier, more professional type of criminal could move in. “Ivory buyers are easy to find now. It’s a race against time to build community support for conservation.”

Tourism is the essential ingredient for all his plans, but tourists themselves are still in short supply, with Zimbabwe’s international reputation as a destination only just starting to recover. Some individuals, however, have made a huge impact: one holidaying Spanish dentist returned with a full surgical team and gave the area its first ever access to dental hygiene. Mark Butcher is hugely proud of that achievement, but he doesn’t lose sight of the greatest benefit a tourist can bring, merely their presence.

“Poachers don’t like to be seen,” he says. “This is the frontline where the war is being fought and tourists who get here are like eyes and ears against the enemy.”

Back in Ngoma, the village that supplies Camelthorn with its staff, we watch people filling up water cans at the pump. Until the new borehole was drilled, villagers were walking 6km for drinking water while the elephants inside the park had better, more reliable supplies. “That’s the kind of anomaly we are tackling,” says Butch. “How can we expect these people to be pro-conservation unless these problems are dealt with?”

Further up the road we are into areas where villagers have yet to see any benefit from the park. We stop at a school, recently renovated by Imvelo, and Vusa hands out books. The children here are just as excited to see visitors, but they aren’t so enthusiastic when Vusa asks if they want to be wildlife guides. One of the boys points to a bird in the book Vusa is showing them. It’s an Indian roller, a gorgeous feathered princess laden with lilac and mauve feathers.

“We kill that one,” he shouts in Ndebele, “Lots of them.”

“Come back in a year,” Vusa says to me. “We’re going to employ people from here at Jozibanini. You’ll see, these attitudes will start to change.”

Way to go

The trip was provided by Rainbow Tours, which has an eight-day Zimbabwe Safari & Victoria Falls Adventure trip from £2,799pp, including stays in Jozibanini, Camelthorn Camp in Hwange national park and Victoria Falls Safari Lodge, flights and transfers, all meals and local drinks, game drives and a school tour at Jozibanini. Airport stay provided by Holiday Extras. Rail travel from York to London provided by East Coast Mainline

Powered by WPeMatico