Gilded Age industrialist Henry Flagler knew a thing or two about tourism; he’s a big reason why St Augustine, West Palm Beach and Miami are the major destinations they are today. In fact, most of Florida owes its modern existence to the great railroad baron, who opened the route south from Jacksonville with his visionary East Coast Railway in the 1880s and built the first hotels that would eventually attract a wealthy clientele.

It makes sense, then, that the Sunshine State’s next big attraction will be a high-speed railway that mimics much of what Flagler pioneered more than 120 years ago.

High-speed rail in the US has a chequered history, with more false starts than a nervous sprinter. Plans have been in place for a national high-speed rail network since 1965, but to this day only the 150mph Acela Express from Boston to Washington DC fits that particular bill. California has committed to an intra-state line that will link its major cities, but don’t hold your breath. The tentative completion date is 2029.

It could also take as many as three million cars off the four-hour-long Orlando-to-Miami drive.

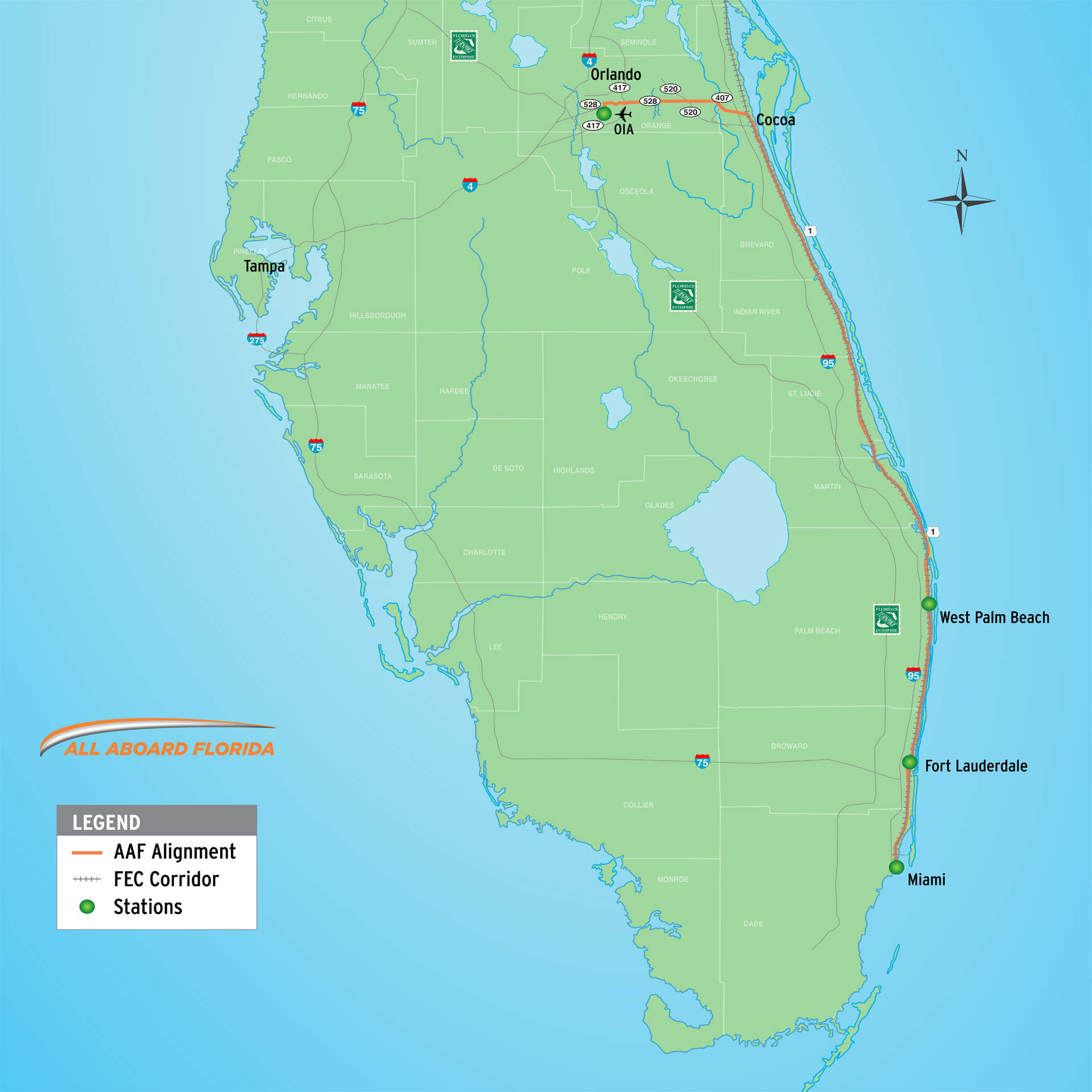

All Aboard Florida’s Brightline service, on the other hand, is set to open in 2017. Starting at Orlando International Airport, the train – reaching top speeds of 120mph – will head east to the coast, and then pick up Flagler’s original route south, stopping in West Palm Beach and Fort Lauderdale before breezing into the city that was almost named “Flagler”, before Henry insisted it take its title from the original Native American settlers, the Myaamiaki, or Miami Indians.

Trains will run 16 times a day in each direction, taking around three hours – considerably quicker than their predecessors – and offering the latest on-board creature comforts, including wi-fi, full dining service and plenty of luggage storage. It could also take as many as three million cars off the four-hour-long Orlando-to-Miami drive.

It is a bold vision for the Sunshine State, with the southeast’s leading railroad historian, professor Seth Bramson, insisting: “It is an incredible initiative that will put billions of dollars into state infrastructure and hundreds of millions into the state treasury. And it is all being done in the tradition of the single most important name in the history of the state.”

The historical side of things began in St Augustine, where Flagler arrived in 1883 and discovered a tourist diamond in the rough, a glittering beach resort area lacking only the glitter, which Flagler promptly supplied in the form of Hotel Ponce de Leon, a 540-room Spanish Renaissance marvel of the age, and its sister property, the Hotel Alcazar.

Today, the Ponce de Leon is the centrepiece of artsy Flagler College, while the Alcazar has become the Lightner Museum, a treasure trove of American Gilded Age antiquities. Another of Flagler’s great edifices, the Casa Monica – which he bought in 1888 – remains a bastion of period grace as one of the oldest hotels in the country.

From St Augustine, Flagler built steadily south, creating his Florida East Coast railway as a gateway for the rich and famous. He acquired the Hotel Ormond just north of Daytona – demolished in 1992 to make way for a condo building – and kept going, chalking up settlements like New Smyrna and Titusville along the Indian River, where manatees and dolphins amused his customers and are still the subject of wildlife cruises today.

The town of Cocoa, just south of Titusville, is also where old meets new for Brightline, with its all-new 40-mile stretch of line from Orlando meeting the original route laid down by Flagler’s men. Heading south, riders will have the same gorgeous coastal views that the “Tycoon in Paradise” (as Flagler was dubbed by the media of the day) afforded his customers for the journey south to West Palm Beach, America’s first purpose-built tourist resort after he arrived in 1894.

Those lucky 19th Century holidaymakers stopped at the massive Hotel Royal Poinciana, at 1,150 rooms the largest hotel in the world as well as the biggest wooden structure on Earth at the time. It catered to 2,000 guests with a staff of 1,700 – and had hallways totalling seven miles in length. Tragically, it was all but destroyed in a 1931 fire, but sister hotel The Breakers – a cathedral of Italian Renaissance style built in 1896 and subsequently rebuilt after fires in 1903 and 1926 – remains as a legacy to the peak of Flagler’s era and still enchants modern visitors today.

Nearby, Henry’s stunning 55-room mansion, Whitehall, has been converted into the ultimate look into his life and times as the Flagler Museum. When it was completed in 1902, at a cost of $2m – the equivalent of almost $2bn today – Whitehall was hailed by the New York Herald as “more wonderful than any palace in Europe, grander and more magnificent than any private dwelling in the world”. And it maintains much of that splendour today.

Further south in Miami – the last stop on the line – there remains another tribute to the railroad’s founder. While his grand Hotel Royal Palm, opened in 1896, failed to survive a 1926 hurricane, the iconic Flagler Monument Island still prevails (albeit with some litter problems). Dedicated to the tycoon himself in 1920 by entrepreneur Carl G Fisher, the man-made island in Biscayne Bay is open to anyone with a boat (or jetski or kayak) and features a central 110ft obelisk and four rather battered allegorical sculptures, each representing a signature aspect of Flagler’s grand legacy to Florida. As a sage nod towards its founder, Miami’s new downtown train station will also be built on the same spot as Flagler’s original, paying homage to his 19th Century vision.

The story of Flagler and his groundbreaking railway culminated in 1912 with the epic extension to Key West, which is widely considered to be the greatest rail construction feat in US history. An engineering marvel to rival the Panama Canal, its 127-mile extent of bridges and railbeds through the Florida Keys –then just a chain of unlinked islands scattered in the rough direction of Cuba – was dubbed “the Eighth Wonder of the World”, and finally opened the whole of the state to a tourist boom that has never ceased.

For more than 20 years, the “Over-Sea Railroad”, as the Keys section was known, was the company’s crowning glory, but it couldn’t survive two hammer blows in quick succession. The Great Depression had forced the railroad to declare bankruptcy in 1931 and, when the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935 ripped through the Keys, there was neither the will nor the financial wherewithal to rebuild the extensive railway wreckage. Instead, the surviving bridges and infrastructure were sold to the state of Florida, which promptly converted the railbeds to roads and turned them into a breathtaking highway. Designated an All American Road in 2009, it is a lasting honour to the man who made it all possible.

A tycoon’s grand contribution

On all his Florida projects, Flagler spent around $50m, or one-third of the state’s entire value in 1912. The Key West extension cost almost two-fifths of that vast sum.

The Florida East Coast railway itself eventually managed to emerge from insolvency and passengers continued to pour into the state until the slow, motor-car induced decline of the railways finally caught up with the company and the passenger services were discontinued in 1968. More prosaic but more profitable, cargo and goods have been the railroad’s stock in trade ever since. The ponderous Amtrak service continues to offer passenger options into South Florida, but using a slower, inland route rather than Flagler’s historic track.

When the first Brightline trains roll in from Orlando next year, it will revive an era of east coast glamour and style not seen since the Gilded Age itself. It’s the perfect way to salute one of the great American pioneers, offering a journey that’s as back to the future as they come.