This post may contain affiliate links. We may earn money or products from the highlighted keywords or companies or banners mentioned in this post.

Some years ago, my family and I paid a visit to the Rainbow Bridge national monument in Utah. It’s a natural stone arch, roughly the same height as the Statue of Liberty, and so remote that it wasn’t located by white people until 1909. It used to require a desert hike of several days to get to the bridge, but ever since the dam turned the Glen Canyon into Lake Powell, it’s only a two-mile stroll from a convenient landing dock. When we arrived, no one was around, apart from a park ranger stationed on the path, waiting for us, ready to answer any questions we might have, and to ask us to refrain from walking under the arch, because it is a site of tremendous religious significance for several Native American tribes.

This federal employee standing in the middle of the desert – engaging, articulate, genial – seemed as much a monument as the bridge itself. I don’t think I’ve ever met anyone who enjoyed his job so much. We took turns posing for photographs wearing his hat.

The photographers came first, dragging their heavy, wet-plate cameras into the wilderness

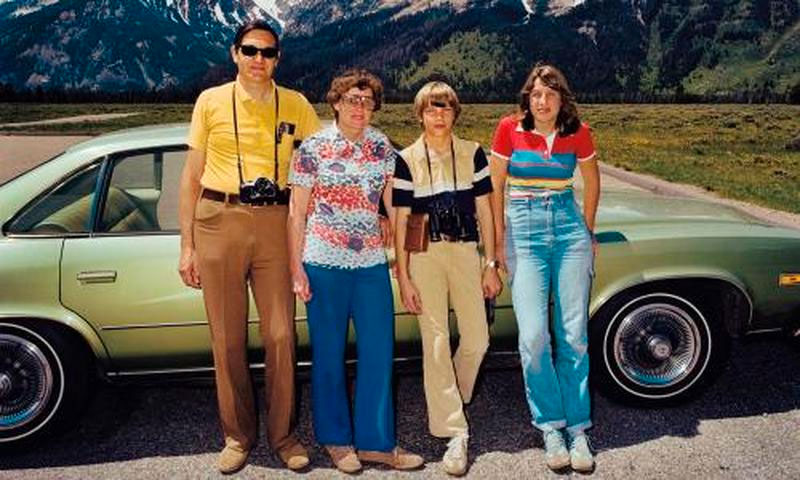

For more than a century, national parks have been the places where Americans come to terms with the immensity of their own landscape, and the juxtaposition is immediately jarring: you find yourself viewing indescribable majesty through the windscreen of the car you drive to work in.

America’s National Park Service has its origins in a forward-thinking, 19th-century effort to save the nation’s spectacular wilderness from exploitation by commercial interests – basically from what had already happened to Niagara Falls, a natural wonder turned tourist trap. In 1864, Abraham Lincoln approved the Yosemite Grant, ceding the Yosemite Valley to the state of California for conservation. In 1872, Yellowstone became America’s first national park, and in 1916 the National Park Service was created and charged with preserving the lands it managed, while also making them accessible to the public.

Chris, Campground Ranger, Tuolumne Meadows Campground, 2014; from the series Yos-E-Mite, by Michael Matthew Woodlee. Photograph: © Michael Matthew Woodlee

In the early days the national parks, most of them in the far west, were pretty inaccessible. It was easier for tourists with money to get to Europe. The photographers came first, dragging their heavy, wet-plate cameras into the wilderness. The advent of the automobile changed all that; the tourists arrived on newly built roads, and they started taking their own pictures. Later still, the photographers started taking pictures of the tourists.

There’s an obvious dichotomy in these twin aims of preservation and access: tourists spoil things. They blot the landscape. They turn raw nature into something consumable. Inevitably, they leave their mark.

I found sharing the trail with strangers in flip-flops excruciating. ‘Look out!’ I wanted to shout. ‘It’s a mile deep!’

Our next stop after the Rainbow Bridge was the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, with its pine forests and panoramic-windowed lodge. The South Rim is the more famous national gawping place – about 90% of canyon visitors congregate there – but the North Rim is still pretty crowded. One is forever ducking out of other people’s pictures. I suffer from acrophobia-by-proxy – I’m afraid of heights on behalf of others – and I found sharing the trail with strangers in flip-flops excruciating. “Look out!” I wanted to shout. “It’s a mile deep!”

But what the photographs collected here capture is an overwhelming sense of fragility. The landscape is invariably vast; the people are specks. National parks may be populated by tourists, but that does not make them tame places. Arguably this incongruity – unconquerable majesty, tourists in T-shirts – is the point of the National Park Service; to bring the one to the other. The rituals we have developed around our encounters with awesome spectacle may seem inadequate but, frankly, what else are you meant to do? You stand, you stare, you take a few pictures. If all else fails, you try on the ranger’s hat. He honestly doesn’t mind. It’s part of his job.

Merced River, Yosemite National Park, California, 13 August 1979, by Stephen Shore. Photograph: © Stephen Shore/Courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York

• These images are taken from Picturing America’s National Parks, published next month by Aperture and George Eastman Museum at £35. To order a copy for £28, go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. An accompanying exhibition runs at George Eastman Museum, New York, from 4 June-2 October; go to eastman.org for details