This post may contain affiliate links. We may earn money or products from the highlighted keywords or companies or banners mentioned in this post.

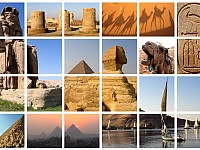

Egypt, deprived of its tourist revenue and entangled in an unprecedented economic crisis, is struggling to preserve its fabulous historical monuments. Egyptian heritage has been maintained by revenues from tourism which has however significantly dropped.

After the 2011 revolution, the dismissal of President Hosni Mubarak, and then that of Islamist President Mohamed Morsi in 2013, political instability and the threat of terrorism have caused foreign visitors to flee. The tourism drop has been felt in many industries. The Ministry of Antiquities is financed in part by admission tickets to museums and historical sites, and thus by tourists as well.

“Since January 2011, our revenues have fallen dramatically. And this has strongly affected the state of Egyptian heritage,” the Minister of Antiquities, Khaled El-Enany, said.

Entry tickets yielded only £300 million ($38.4 million) in 2015, compared to $1.3 billion in 2010 ($220 million dollars), according to official figures and foreign exchange rates at the time. At the same time, the number of tourists fell from 15 to 6.3 million a year. This trend further continued in 2016.

From the pyramid of Giza—the only one of the seven wonders of the world still visible today—to the temples of upper Egypt, passing through Islamic churches and buildings, Egyptian heritage requires permanent preservation efforts which are threatened by the tourism drop.

“Antiquities are deteriorating everywhere,” said the archaeologist Zahi Hawass, former Minister of Antiquities. “With the lack of funds, we cannot restore anything. Look at how dark the museum in Cairo is,” continued the authority of the world of Egyptology, for whom the government is unable to compensate due to the national decline in revenue. Especially since the government has to pay approximately 38,000 employees of the administration of Antiquities: workers, technicians, Egyptologists, and inspectors.

The burden is therefore heavy at a time when Egypt is experiencing slow increase, spectacular inflation, and shortages of various products.

While waiting for the return of the tourists, Mr. El-Enany is attempting to limit the damage. “To increase revenues, I am trying to do some extra activities,” he said, citing the opening of the Cairo Museum at night and the creation of new annual passes to attract more Egyptians to the archaeological sites.

At the same time, patrons, archaeological missions, foreign or mixed, continue to contribute to the preservation of Egyptian heritage. But outside help cannot cover everything.

On the ground, “the priority is restorations, but there are excavations that have been halted because of the lack of funding,” lamented Mrs. Fayza Haikal, an Egyptologist and professor at the American University in Cairo, while acknowledging that “the excavations that have waited 5,000 years can still wait.”

Most restorations, too, have to wait. “At the very least, we identify the buildings that need restoration, and we do the minimum to keep them up to a proper restoration,” she explained.

Mr. El-Enany also advocates for the exploitation of more sites, such as the tombs of Nefertari or Seti I in Luxor, which have just reopened to the public.

The museum of Malawi, in the province of Minya, which was looted in 2013 at the height of political unrest, is also welcoming visitors again. The Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM), a flagship project to house pharaonic collections at the foot of the Giza pyramids, is to be opened, at least in part, in 2018, with the support of Japanese cooperation.

For some projects, the ministry can also obtain special funds, such as this year for the synagogue of Alexandria and the Abu Mena church, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. “But this will not replace the lost revenue due to the tourism drop,” said El-Enany.

Pending a possible takeover, Mr. Hawass, also adviser to the minister, advocates the growth of the number of exhibitions abroad. “Why keep Tutankhamen at the Cairo Museum in a dark corner? Tutankhamun can earn money,” and, being loaned to other countries, “pay the ministry’s wages for 10 years,” he said.